FBI Tells Apple, “Just This Once.” Why a One Time Exception is a Slippery Slope

FBI Tells Apple, “Just This Once.” Why a One Time Exception is a Slippery Slope

Major news outlets and social media are ablaze today, with self-proclaimed pundits offering their analysis on Apple CEO Tim Cook’s recent Message to Customers.

A US District Court has issued a court order in an attempt to force Apple to “assist law enforcement agents in obtaining access to the data” on deceased San Bernardino terrorist Syed Rizwan Farook’s iPhone 5C.

Typical with any large-scale public event, much of what passes as informed opinion is, in fact, not so well-informed as it might pretend to be. In this article, I intend to take a look at the facts of the case, before digging into the ramifications of the court order and whether or not it’s technically feasible for Apple to comply.

A Situational Overview

First, a little background information is in order. FBI data forensics have had this iPhone 5C in their possession for about two months, this is clear by backtracking to the date of the San Bernardino incident. Based on the contents of the court order, it can be presumed that the’ve been thwarted from gaining access to the contents of the device, due to the software lock on the phone. Circumvention of this software lock is the primary documented goal of the order, from which “technical assistance” has been demanded from Apple, the manufacturer of the device.

It can also safely be assumed that the version of the OS on the phone is greater than iOS 8, which was the first iteration of iOS to include “full encryption” of data contained on the device. This is also not the first time the Federal government has demanded that Apple assist them in dealing with encrypted devices made by Apple. The outcome of that case has still not been decided and Apple has requested that the court make a decision on whether the government can compel Apple to assist with the unlocking or not.

So understandably, the FBI feels that there’s information on the phone that may be useful either as part of the San Bernardino investigation, or in discovering evidence of future, or aborted attacks of a similar nature. Though they won’t know this without unlocking the phone first.

The nature of this potential evidence wouldn’t already be known, though useful information could have already been gathered. Information like the call records of Farook, (who he called, who called him, when and with what frequency) could have already been obtained from Verizon via court orders or subpoenas. Similar information about the electronic correspondence between the shooter and his contacts may have already been obtained directly from the service providers he used (eg: Google, Yahoo, other email providers.) Unless of course, Farook ran his own private email server like certain Presidential candidates, which is unlikely.

From the official narrative, we are to believe that the FBI has been manually attempting to unlock the iPhone in question over the last two months and have failed thus far. They’ve made no mention of other avenues of attack, despite there being a number of commercially available (and in at least one case, Federal intelligence-community funded) forensics tools in existence.

They then requested that the US District Court issue a court order, compelling Apple to provide the “technical assistance” they claim they need to access the data on the phone. Apple has issued their own response, in public, to that court order and it’s safe to assume that they’ve also replied, or will within the five day window provided by the court order, through more official channels.

The Court Order

Next, let’s take a look at the court order, itself, ED 15-0451M, as issued by the United States District Court for Central District of California:

For good cause shown, IT IS HEREBY ORDERED that:

-

Apple shall assist in enabling the search of a cellular telephone, Apple make: iPhone 5C, Model A1532, P/N: MGFG2LL/A, S/N: FFMNQ3MTG2DJ, IMEI: 358820052301412, on the Verizon Network, (the “SUBJECT DEVICE”) pursuant to a warrant of this Court by providing reasonable technical assistance to assist law enforcement agents in obtaining access to the data on the SUBJECT DEVICE.

-

Apple’s reasonable technical assistance shall accomplish the following three important functions: (1) it will bypass or disable the auto-erase function whether or not it has been enabled; (2) it will enable the FBI to submit passcode to the SUBJECT DEVICE for testing electronically via the physical device port, Bluetooth, Wi-Fi, or other protocol available on the SUBJECT DEVICE; and (3) it will ensure that when the FBI submits passcode to the SUBJECT DEVICE, software running on the device will not purposefully introduce any additional delay between passcode attempts beyond what is incurred by Apple hardware.

-

Apple’s reasonable technical assistance may include, but is not limited to: providing the FBI with a signed iPhone Software file, recovery bundle, or other Software Image File (“SIF”) that can be loaded onto the SUBJECT DEVICE. The SIF will load and run from Random Access Memory (“RAM”) and will not modify the iOS on the actual phone, the user data partition or system partition on the device’s flash memory. The SIF will be coded by Apple with a unique identifier of the phone so that the SIF would only load and execute on the SUBJECT DEVICE. The SIF will be loaded via Device Firmware Upgrade (“DFU”) mode, recovery mode, or other applicable mode available to the FBI. Once active on the SUBJECT DEVICE, the SIF will accomplish the three functions specified in paragraph 2. The SIF will be loaded on the SUBJECT DEVICE at either a government facility, or alternatively, at an Apple facility; if the latter, Apple shall provide the government with remote access to the SUBJECT DEVICE through a computer allowing the government to conduct passcode recovery analysis.

-

If Apple determines that it can achieve the three functions stated above in paragraph 2, as well as the functionality set forth in paragraph 3, using an alternate technological means from that recommended by the government, and the government concurs, Apple may comply with this Order in that way.

-

Apple shall advise the government of the reasonable cost of providing this service.

-

Although Apple shall make reasonable efforts to maintain the integrity of data on the SUBJECT DEVICE, Apple shall not be required to maintain copies of any user data as a result of the assistance ordered herein. All evidence preservation shall remain the responsibility of law enforcement agents.

-

To the extent that Apple believes that compliance with this Order would be unreasonably burdensome, it may make an application to this Court for relief within five business days of receipt of the Order.

Technical Feasibility of the Court Order

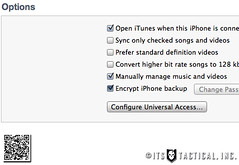

To examine the technical feasibility, we must first have a solid understanding of what’s being demanded here. In examining the actual text of the court order, it becomes fairly clear that what the FBI wants is a means to circumvent the iOS software lock setting to automatically wipe the phone after ten failed attempts at entering a passcode.

It’s not clear whether they know if that setting is currently on or off and they may honestly not know, having not risked ten consecutive unlock attempts at a time. They also want to be able to enter the passcode electronically, rather than having someone sit there and type one passcode attempt at a time. They’ve demanded that the ability to enter passcode attempts via the Lightning port, Bluetooth or WiFi, be added to the phone. Finally, they’ve demanded that the passcode entry process not incur any non-hardware defined delays.

All of these features they’re demanding Apple provide, by means of creating a bootable version of the iPhone operating system, “iOS,” which either the Feds or Apple would install via the “firmware update process,” a “recovery mode” or some other unspecified “mode” of installation. They’ve gone ahead and specified that this modified version of the operating system, which does not currently exist, be created and then loaded only into the device’s RAM and not the flash memory.

What they haven’t actually demanded is that Apple provide a “backdoor key” to the encryption used by the device. Instead, they’ve asked that an entirely new version of the OS be developed to only run on this particular iPhone and that this version allow them infinite chances at brute forcing their way into the phone by electronic means, without defaulting to a self-reset of the entire device.

Is it possible for Apple to create a brand new version of the iOS that could turn off the auto-destruct feature? Technically and probably, yes. Is it possible for them to allow for unlocking attempts by some electronic means other than finger-on-touch-screen? Possibly, though this is more complicated than the layman may expect.

Finally, is it possible to make sure that no software-induced delays to the brute forcing attempts to break into the phone are introduced? Sure. But doing these things is neither simple or fast. Worse yet, the creation of this entirely separate iOS version for one-time Federal use is both a bad idea and sets a bad precedent for future uses, despite a one-line half-assed assurance in a poorly-worded court order that they only want it for this one phone, this one time.

Ramifications of Compliance with the Court Order

Despite the documented intent to have this “tool” for use only in this one case, this isn’t the first time they’ve asked for help in circumventing “locks” on smart phones from Apple. Once a tool like this exists, it will exist forever. Much like saying something stupid on the Internet, once it’s out there, it stays out there.

You can delete bad data, but chances are good there’s a copy of that data floating around from now until the end of time. Once you give the FBI a means of circumventing safeguards, they’ll either modify that one-time-use software to use again, or they’ll demand another one-time-use version of the operating system be developed the next time there’s a “unique case” that “requires” it.

Worse still, once that tool exists, can you trust that it won’t propagate? Are the FBI’s systems so secure that no bad actor could ever obtain a copy of that tool and use it with malicious intent? For that matter, can you even trust that no one within the FBI would never surreptitiously copy it and use it for their own personal reasons?

Currently, decryption is a computation-intense process. In time, as we get closer to having functional quantum computing power (and the Federal government is going to have it before anyone else does), decryption will become nearly trivial. In that sense, we’re in a societal window wherein encryption, for the moment, can be trusted to safeguard a person’s data against unlawful or even lawful attempts to thwart those protections provided by it.

Encryption does not make a distinction about the intentions of the encryption user; it works mathematically to render the encrypted data unreadable by anyone without the authority to decrypt it, whether that person is good or bad, engaged in lawful or illegal behavior. Encryption protects the privacy rights we all have.

Demanding that a corporation provide a loophole, or “back door” into that process is a dangerous precedent to set, for several reasons. First, it may not even be possible to do and second, once that “back door” is open, even if those who demand it promise to never do it again (and believe me, they will do it again), it remains open forever.

Other Options for Law Enforcement

It seems somewhat strange to think that the FBI has merely been tinkering at guessing the passcode for this particular phone, when forensics tools for just these purposes already exist. Pulling a copy of the entire device’s memory would be a good first step (and, in fact, is the Standard Operating Procedure when performing forensics on a data device), then using tools like Black Bag Technologies’ “Black Light” to analyze that data would help.

As an interesting side-note, “Black Bag Technologies” received funding from the CIA’s investment venture capital firm, In-Q-Tel, so their product suite is definitely a known quantity to the US Intelligence Community. There are other tools available as well, like Oxygen Forensics set of tools. Pulling useful data from seized devices is a known science and there are a number of experts in this field that would be more than willing to help.

All that said, I’d like to believe that the FBI is much more capable of analyzing data on the devices of criminal suspects than this court order would indicate. It either inspires little confidence in the technical forensics abilities at the federal agency, or is indicative of a political agenda to set a legal precedent for demanding major corporations go to ridiculous lengths to allow “back door” access that they make promises to never misuse in the future.

In that sense, I applaud Apple responding in the manner in which they have. As they’ve stated, they’re more than willing to comply with court orders for data contained on their own internal servers if legally mandated to, but providing a proverbial “one time key” for this sort of thing is a bad idea, both technically and ethically. By refusing to do so and making the public case for their refusal, they’re bringing the issue to a wide audience, who should rightly be involved in any such public discussion about the ramifications of such access and what it means to each of us, both criminal and non-criminal.

No one wants more terrorism in this country or anywhere else (well, no one but terrorists), but we have processes in place that preserve the liberty we currently enjoy and whittling those protections away is bad for all of us.

Update: In an attempt to answer more on the questions being raised on this issue, Apple has released the following information here: http://www.apple.com/customer-letter/answers/

Discussion