Climbing the Tower: How to Recognize You’re Off Course and Pursue Mentorship

Climbing the Tower: How to Recognize You’re Off Course and Pursue Mentorship

The other day, I saw a beautiful sunset that lit up the entire night sky in orange, red and purple. There were just enough clouds in the sky to help transform the blue atmosphere into a tapestry that would make even the most stoic amongst us pause, look up and appreciate the world we live in; if even just for a moment.

It gave me pause as well. Not for the reason you may suspect, but rather because it made me think of how many sunsets I’ve seen over the years, equal in brilliance and how few of them I could remember. We always think that we’ll remember the things that happen to us and these events seem very important at the time. They can fill our minds as we live them and distract us when we’re away, but with enough time between us and the events, they seem to just float away. Memories are like a mist in the air that’s different from its surroundings in one moment and then a part of it the next. Perhaps lost forever.

This isn’t true for all memories obviously, just the bulk of the human experience. There are however, certain moments in life that we’ll carry to our graves. These are the moments that had a dramatic impact on us at the time and those that we have practice reliving over and over in our minds. When we dwell on certain events, we’re practicing reliving them and burning them into our minds to recall later, whether we really want to or not.

There are some things that I’ll never forget. I’ll always remember a 40 mile hike I made with my best friends in junior high. I’ll never forget my first kiss, my first public speaking event, the time I got cheated on in college, getting rolled back in BUDs (SEAL training), or eventually getting a Trident pinned on my chest.

Everyone remembers the milestones like children being born, wedding days, promotions and so on. These are things that made me a better person, but I want to focus on some of the memories that made me a better teammate. These had nothing to do with accomplishment, but everything to do with mentorship and accountability.

It can be a challenge to learn from our successes, but the failures, those seem to dig in. When we fall just short and are made aware of our shortcomings, we progress as teammates. Those are some of the lessons and hard conversations that I’ll never forget. The times when others decided to care enough and invest enough to say what needed to be said.

If You’re Not Early, You’re Late

When I was a new guy, meaning that I’d made it through SEAL training but had zero experience, I showed up to the SEAL team pretty cocky. I don’t know why that was. In truth, I was the shortest guy there, had been rolled back in training due to poor swim times and had never deployed. Still, in my youth, I had a tendency to see myself as above the situation somehow. Maybe most people feel that way on the inside when they’re young and have accomplished a thing or two. I can honestly say that I was fully capable of becoming what we call in the teams a “turd.” As I’m sure you can tell, that isn’t a compliment. Fortunately, right when I needed it most, I found someone who would make an impact on me.

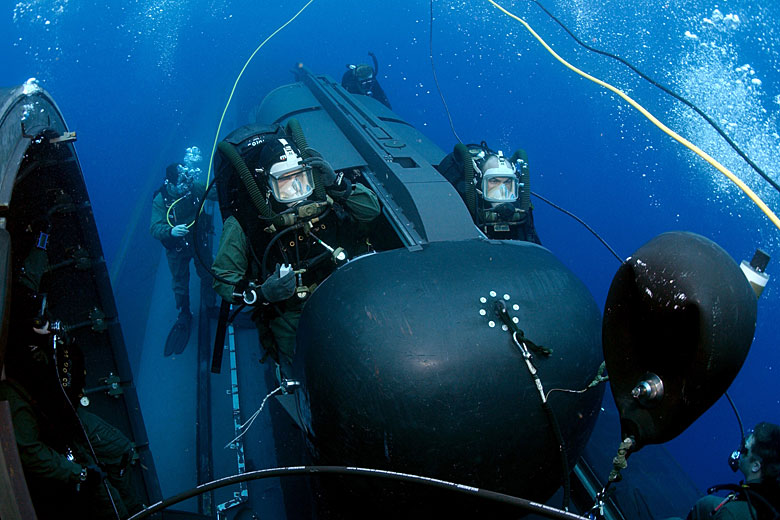

It was a typical day of training. We would muster at 0900 for a meeting, break for a workout, begin prepping the SEAL Delivery Vehicle (miniature submarine) and all necessary diving equipment and then finally begin our training dive after the sun had gone down behind the Hawaiian island of Oahu’s horizon. I’d decided to ride my motorcycle to work that day and had received some hard words at the gate about not wearing the appropriate safety equipment for a motorcycle on a Naval base. Of course, being young and cocky, I had to have the last word and this exchange made me late for our 0900 meeting.

I was late walking in the door, but only by about two minutes. My chief, who we’ll call Jim for the purpose of this story, made a comment that went something like, “Nice of you to join us this morning,” as I found a chair. The rest of my platoon were already gathered and waiting on a full head count to begin. An important note here is that a new guy in a SEAL platoon is expected to show up to all meetings 15 minutes early. A common saying is, “If you’re not early, you’re late”.

In response to my two minutes of tardiness, my platoon Chief Jim asked me to stay behind after he ended the meeting. His face wasn’t overly stern and didn’t show even an ounce of anger. He spoke plainly and with little inflection in his voice. “It’s obviously not that big of a deal, but being late is probably not the best way to start the day,” he said with a slight chuckle and dismissive hand gestures. “No drama, but go ahead and fill a rucksack (military speak for backpack) with 50 pounds of weight and run up the para-loft tower one time for every guy in the platoon. Then we’re even.” I thought he was joking at first, considering the para-loft tower was five stories high and we had 20 guys in our platoon. It seemed a little bit harsh for a two minute infraction. Still, I figured it may be some kind of test, so I would play the game.

The Long Night

I went downstairs and filled up my rucksack with 50 pounds. As I threw it on my back, ready to walk to the tower, I heard Jim’s voice, who’d obviously followed me down, “You can’t do it now bro, that would be in place of your workout and wouldn’t even be a punishment. You have to do it after work. Let’s go get a lift.” Now I knew that he was just giving me a hard time. It had seemed like a joke when he told me and he obviously wasn’t even angry. I dropped the bag and we went to workout together for an hour or so before beginning our gear prep for a night dive. For the rest of the day, Jim never brought up my morning infraction and it seemed that I was in the clear.

Night fell and we splashed the SDV into the water. I was the pilot and we had a long dive in front of us. I won’t bore you with the specifics but we didn’t finish until well after midnight. When a dive is over, the work isn’t. There’s work to be done on the SDV, as well as dismantling the complicated mixed-gas systems we use. We always clean up the team gear first, then your swim buddy’s gear, then at the end of it all, you take care of your gear.

I remember rinsing my wetsuit, dive fins and mask when Jim walked up and said, “Don’t forget the rucksack Brother.” My heart sank with the realization that a punishment that clearly did not fit the crime was still looming in my painful future.

Needless to say, I was furious. Despite my anger, I knew better than to show weakness on my face or express anything other than good humor to my platoon mates, who would’ve surely been brutal had they smelled blood. Instead of voicing my opinion, I grabbed my rucksack and began the walk of shame to the para-loft tower. As I walked closer I could see that Jim was standing at the door of the tower. This fueled my anger at first. Did he not trust that I would do it? Did he bring a scale to weigh my bag and make sure I wasn’t cheating? As I got closer, I noticed that there was something laying at Jim’s side, but it wasn’t a scale. It was a rucksack.

The Climb

Upon my approach, Jim picked up the ruck and threw it on his back. He told me that my failures are his failures. That he’s the leader of the platoon and ultimately responsible for my actions. My pain would be his pain. That was all that he said, nothing more. He turned and ran up the first flight of stairs and I followed. We ran every flight of stairs together that night. Five stories, twenty times, with 50 pounds on our backs after a 14 hour work day. He never gave me a hard time or said anything more about it during those painful hours. In fact, we found ourselves laughing. We talked about God, family, the mission and whatever else popped into our heads. I knew in that moment that I could trust this man. I knew that he cared enough to invest in me and show me a better way. Jim cared enough to teach and I was happy to learn.

Throughout the rest of that platoon I’d look to Jim as a guide. When we started a new block of training, I’d look at his gear and make sure that mine looked exactly like his. I figured he’d learned a thing in his 7 deployments and that I could save a lot of time and possibly pain, if I modeled my gear, equipment, rucksack, weapon system and even daily routine after him. I learned about raising children, being a husband and faith from our conversations. Eventually, on deployment, we’d pray together before going out the door on a high level mission. Not too long after that, we stood side by side as they pinned Bronze Stars on our chests at an award ceremony.

I was young, talented, cocky and in desperate need of a mentor. When I found one and saw that value, I held on for dear life. I became a better operator for the experience, but I also became a better man. Perhaps more importantly, I learned quite a bit about how to lead a collection of high octane individuals. One of the most essential tricks of the trade for Elite individuals is to find solid mentorship. Avoid the learning curve cost associated with operating at the highest level by sticking close to someone who has faced the issues you’re about to face and overcome. Listen, learn and take notes. I had been successful, but talent would only take me so far. I was charging at full steam, but my course was just a touch off.

The Difference in Two Degrees

To put it in another way, I was navigating my proverbial ship in the correct general direction but was off by a degree or two. I’ll take a moment to explain that for anyone who hasn’t experienced navigation by compass. When I want to travel somewhere, say in a boat without a GPS, I need to know where I currently am, where I want to be and the bearing that will get me there. I need all three pieces of information for accurate navigation on the water without any landmarks.

If I need to travel on a bearing of 270 degrees for 100 meters, then I position myself to fly that bearing and start moving. For a distance of only 100 meters, if I get sloppy and travel a bearing of 272, it will be of little consequence and I’ll still get to where I need to be. However if I travel say, 1000 meters, that 2 degree difference begins to amount to more deviation. This is to say that I’ve deviated from my intended course which has left me in a different location then where I originally set out to be.

If intend to land on the center of an island but have allowed 2 degrees of deviation in my navigation, then I might actually hit the southern tip. If the island is small enough, then I may miss it all together. My best case is that I can use the light to see it and make a course correction at the last minute. Now imagine that I’m leaving Los Angeles California and I shoot a bearing that should land me on Hawaii. With no GPS or landmarks, I shoot a bearing and begin traveling. At times I lose focus and look away, distracted by the world around me. Maybe the wind blows and I lose the wheel just for a moment.

Whatever the reason, all of this distraction, external influence and human error allows for about 2 degrees of deviation. Will I ever get to Hawaii? Will I even see it on the horizon? Will the first land that I see be the Philippines?

The role of a mentor is to observe who the person is, where they are, where they want to be and then to provide the necessary course correction. That’s the friction that allows iron to sharpen iron. We’ve all needed a course correction in our lives. If you’re an experienced member of the team, a coach or even a junior person who’s identified the need, then it’s your obligation to point out the current deviation. Getting the ship back on track may be a team effort, but it all starts with a spark.

Conclusion

Great teams have powerful mentors who allow friction and discourse when the blade is dull, who take ownership of their actions and the actions of their teammates, who lead by the example they set and the words that back it up and who care more about the course of the ship then the temporary feelings of its crew. Have the hard conversation and allow them to be had with you.

If you need a mentor, find one. Share your course and allow them to help identify the external influences that are pulling you off course. If you see that someone needs a course correction themselves, then provide it with grace and humility. Step up to the plate and invest in your teammates. After all, you’re all in the same boat. Embrace it!

Editor-in-Chief’s Note: Nick recently left the Navy after serving for 10 years as a Navy SEAL with multiple deployments, having been awarded the Bronze Star for operations in austere environments. Nick’s been with us since the beginning here at ITS as a Features Writer.

Discussion