Backcountry Emergencies: Why You Should Learn How To Identify Spinal Injuries

Backcountry Emergencies: Why You Should Learn How To Identify Spinal Injuries

Imagine you and your teenage son are out for a day hike in the backcountry. He’s admiring the view from atop a cliff and slips on some loose gravel; falling over the edge and landing on a ledge about 20 feet down.

You can access him from a path that leads down to the ledge and when you get to him, he’s just starting to wake up, having knocked himself unconscious. You have basic first aid training and you remember that any fall from a distance greater than the “patient’s height” is super scary and you should make sure they don’t move in case they “broke their neck.” You know he lost consciousness, but he seems “with it” now.

Checking your cell phone, you see you’ve got no signal. You estimate that you’re about 4 miles from your vehicle, parked at the trailhead.

The trailhead is about an hour’s drive from the closest town, which you recall had not much more than a gas station. What do you do?

Do you leave him, hike back to the vehicle and go get help?

You estimate you’re about 2 hours from the town and maybe an hour beyond that from being able to get some sort of medical help to the town. After that, it’ll be an hour drive back up the road to the trailhead.

Based on the mechanism of injury, EMS will likely want to backboard your son. This means you’ll also need more help to safely carry him out. You figure out you’ll need eight people to safely carry out an immobilized patient (you can do it with six, but you’re putting the rescuers at increased risk). Extracting an immobilized patient out on a trail increases the time. So, let’s demonstrate a timeline:

12:00 – Your son falls 20 feet over a cliff knocking himself unconscious.

12:05 – After getting to him, you find him now conscious. You decide to go get help and instruct him not to move, as you’re afraid he “broke his back.”

13:00 – You make it back to your car at the trailhead and begin driving into town.

14:00 – After reaching the town, you’re able to activate EMS (who also actives search and rescue).

15:00 – EMS arrives to the town.

15:30 – Search and Rescue arrives to the town.

16:30 – Everyone is present at the trailhead.

18:00 – All personnel arrive at the accident scene (it was a bit slower since extraction equipment was needed).

18:15 – Your son is assessed and found to be in mild sub-acute hypothermia from laying on the ground not moving for the past 6 hours. He’s strapped to a backboard which is then loaded into a transport basket.

20:00 – All personnel make it back to the trailhead.

22:00 – The group arrives at the hospital.

23:00 – Your son is finally able to get in for an X-ray.

23:30 – The X-ray imagery is assessed. Coupled with doctor’s physical examination, your son’s spine is “cleared.” However, it’s discovered that he has significant tissue break down on his shoulder blades and hips from laying on a hard surface for nearly 12 hours and not moving. If only there was a better way…

Sure, there’s a bit of fluff in that scenario, but it’s honestly not that far from what actually happens most times.

Background

One of the “sacred cows” in EMS is the idea that during any kind of significant trauma everyone, “buys a backboard” (this is currently changing, albeit slowly). Meaning if you’re involved in a “high velocity impact” (e.g. a car accident, fall from height, gunshot to your torso) and you engage EMS, you’re more than likely going to be strapped to a backboard, as well as having a cervical collar applied.

You’re going to be transported on that hard plastic board and dropped off at a hospital. Here, you may spend anywhere from an hour to several hours, completely immobilized. You generally won’t be released from the board until you’ve undergone a strict examination and most likely had some sort of imagery done.

We generally think of that as an acceptable practice given the type of injury that can occur from “spine” damage.

The risk is that a full transection of your spinal cord (that doesn’t outright kill you) can lead to complete tetraplegia (or quadriplegia, if you prefer). Pretty scary, right? Okay, so what’s the actual incidence of this happening? Before we discuss the answer to that question, let’s talk about some anatomy.

What is “C-Spine” Anyway?

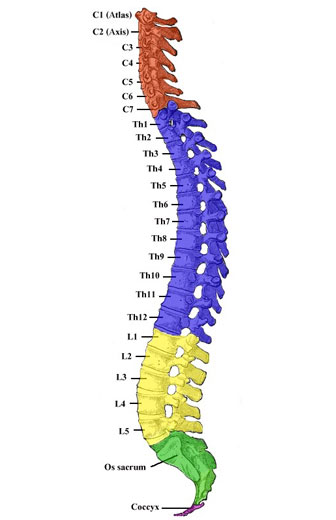

To understand C-Spine (and injuries to the spine) we need to understand the anatomy of the spine as a whole.

Regions of the spinal column.

Specifically we need to differentiate two main components of the spine; the column and cord.

The spinal column itself is a strong bony structure that provides stability and support of our trunk (it’s one of the reasons we’re able to walk upright).

It also protects the spinal cord, which is the main communication line in the body, sending and receiving messages from all parts of your body. It also has redundancy built in.

The cord is contained inside that hollow spot in the middle of the spinal column. It’s surrounded by a cushioning layer of cerebrospinal fluid, all of which is contained by dense fibrous layers of tissue called the meninges. The meninges are further separated from the spinal column by fat.

The heavier and thicker aspects of the spinal column are generally less flexible (your lumbar and coccyx, or lower back and tailbone) while the lighter and thinner structures are more mobile (such as your cervical spine, or your neck).

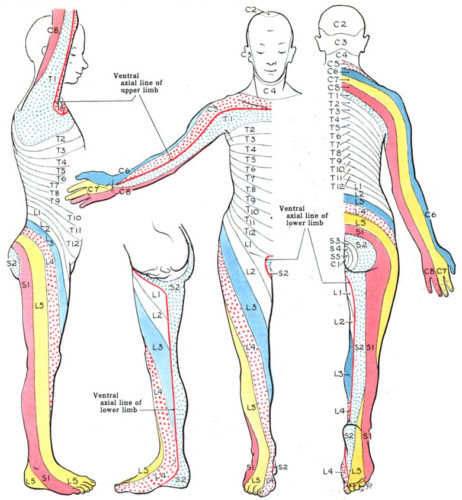

Dermatomes represent nerve pathways we can use to test sensory inputs on the body.

Between the two, it’s generally easier to injure the cord in the lighter and thinner sections and more probable to injury the column in the lower sections.

To injure the cord and have motor or sensory problems, you have to have significant enough trauma to bypass all of the other protective structures, all with enough remaining energy to disrupt the cord. If you’re having trouble tracking, it basically boils down to significant enough trauma.

Why Should We Bother To Clear a Spine?

Okay, so let’s get back to the incidence of actual injury. The National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center (NSCISC) has been tracking spine injuries from at least 1973. They estimate the annual incidence of spinal cord injury in the U.S. is 40 cases per million individuals, which is roughly 12,500 total (assuming a population of 313 million).

That number does not include those that died at the scene. That is four thousandth’s of a percent, or 0.0039%. Only 14% of those cases resulted in the worst case, complete tetraplegia; with another 20% in complete paraplegia.

We’re going to spit ball a little bit of math here, as statistically the error makes little difference. In 2015, of the recorded spinal cord injuries, 33% of those were from auto accidents, 22% were from falls and 15% were from gunshot wounds.

“But Tom,” you say, “better to be safe than sorry, right?” I’m going to argue that context is everything. If you had a major car accident 5 minutes from a trauma center, then sure, hop on that backboard. Roughly 4,125 spinal cord injuries came from auto accidents. 1,403 of those resulted in a complete transection (either tetraplegia or paraplegia). That means that hundreds of thousands of people are needlessly put on a backboard.

Now let’s assume that 100% of all falls humans took in the backcountry from going over a cliff resulted in cord damage (even though that’s absurd). That’s 2,750 total injuries. We could clean up the math a bit and correct for numbers of people falling in the backcountry opposed to urban environments, but we’ll leave it as is for now.

The point of all of that gross math is that damaging your spinal cord is a very rare event, especially in the context of delayed access to medical care.

Apply all of that math to the scenario we started this post with. If we can walk your son out and drive him to the hospital, we should do so, rather than increase the overall risk of the event (risk to rescuers, potential of increasing complications to our patient, etc).

How to “Clear” a Spine

Mechanically, clearing a spine is very simple. Once the following conditions are met, you can have reasonable assurance there’s no cord damage.

- Your patient must be able to discriminate between dull and sharp sensations at all four extremities.

- The patient must be able to move all four extremities, mechanically demonstrating push and pull against resistance.

- Your patient must not have any point tenderness to their spinal column.

To make these tests successful, you must have a patient that can appropriately respond to questions. Not intoxicated, completely “freaked out” or distracted by an injury, etc. They have to be able to respond to questions, follow directions and be able to tell you if something hurts.

You can do the following steps in any order. If you discover anything along the way, keep going with the rest of the test and keep good notes.

- Palpate (examine by touch) along the entire length of the spine.

- Check push and pull function on both of their hands and both of their feet.

- Check for sharp and dull discrimination on both hands and feet.

Palpating the Spine

Using your index fingers (or thumbs), press firmly on each and every vertebrae.

If the patient reports “point tenderness” (which is akin to having a burning match head pressed on that spot during the palpation) you can assume there’s damage to the column. We’re not talking about an ache or soreness, this is legit acute pain at a specific spot.

Motor Check

Feet are easy. Have the patient “step on the gas” while you provide resistance. Do both sides at the same time. Does it feel equal and strong? Good. If not, make note of that.

Now have the patient try to touch their big toe to their knee on the same leg while you provide resistance. Does it feel equal and strong? Good. If not, make note of that.

Hands are a little trickier, but still easy. Have the patient bend their arms to 90 degrees with upper arms tight at their sides. Then have them fold their wrists toward their midline.

You’re going to apply resistance to the backs of their hands and have them try and push you away.

Then hook your hands over theirs and have them pull toward themselves against resistance. If the patient has new weakness on any limb you can assume that there is cord damage.

Sensory Check

Find something sharp that’s not a knife, as stabbing your patient isn’t an appropriate way to check. A pine needle works great, as does the corner of a stiff page. Something like a ball point pen isn’t sharp enough.

Find something dull and soft. Things like the the back of a pine needle or book binding work great.

Have the patient close their eyes. Ask them to tell you what they feel and where they feel it. Then poke them gently with the sharp object on the left and right of their forehead. Repeat the same with the dull object by gently brushing it across their forehead (left and right side). For this, you’re getting a baseline.

Next, with their eyes still closed, check sharp and dull on the back of their hands. I’d recommend testing in a couple places (thumb side and pinky side).

Repeat on the little toe side of their feet. If you can’t access the feet for some reason, you can go to the outside of their leg.

They should respond appropriately for each test. If they have any new inability to discriminate dull/sharp (or feel anything), you can assume there’s cord damage and you should note down where and what failed.

How Does This Help Us?

Now it’s judgement time with you and your patient. If you come up with no findings, congratulations! Your patient is clear. They may be sore, but their spinal column and cord should be fine. They may want to get checked out, but they definitely don’t need a backboard and C-Collar.

If they have column damage but no cord damage, I’d be comfortable walking them out; assuming they’re otherwise physically capable and willing to of do so. Obviously go slow and provide support, as you want to prevent further falls.

If they have cord damage, which will almost always be associated with column damage, I’d recommend getting them comfortable and protecting them from the environment. They’ll likely need to be carried out to minimize any further damage.

However, remember those notes you were taking? What happens when the body is injured? It swells. What does swelling eventually do? Goes away. Peak swelling occurs within 24 hours. There’s a potential your patient has some deficit right now, due to swelling.

Chances are, if you check back in a while and repeat the test, they may be able to pass. Keep in mind this won’t happen in all cases and you should not delay evacuation and access to treatment just to perform another check. Every situation is different and you should have as many tools in your toolbox as you can.

What Now?

Like many other topics, medicine is a skill set. Sure there’s a decent amount of schooling to become a provider (a lot of it being exposure to actual patients), but most of the base concepts are simple. Spine clearing is a very useful skill, especially if you spend time in areas with reduced access to medicine and engage in risky activities.

Practice this exam and become comfortable with the mechanics of it. Teach your significant others, kids and anyone you may go on adventures with. It’s an easy diagnostic you can use to rule out a serious injury and in the process, save a significant amount of time and resources.

Editor-in-Chief’s Note: Tom Rader is a former Navy Corpsman that spent some time bumbling around the deserts of Iraq with a Marine Recon unit, kicking in tent flaps and harassing sheep. Prior to that he was a paramedic somewhere in DFW, also doing some Executive Protection work between shifts. Now that those exciting days are behind him, he has embraced his inner “Warrior Hippie” and assaults 14er in his sandals and beard, or engages in rucking adventure challenges while consuming craft beer. To fund these adventures, he writes medical software and builds websites and mobile apps. He hopes that his posts will help you find solid gear that will survive whatever you can throw at it–he is known (in certain circles) for his curse…ahem, ability…to find the breaking point of anything.

Discussion