LandNav 101: Introduction to Map Margins

LandNav 101: Introduction to Map Margins

In our last article on Land Navigation, Intro to Map Terminology, we introduced you to our LandNav series and went over the most common terms that get thrown around when dealing with maps.

Today we’ll be addressing what all those things in the margins of your map mean and how to best use them to your advantage when navigating.

The margins of a topographic map are rich with information. For the LandNav 101 series, we are going to be operating strictly against USGS maps. While other cartographic entities may vary their margin layout, most will contain all of the details covered herein.

Area and Scale

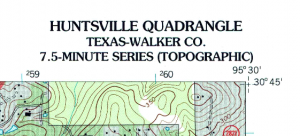

What’s the first thing most people do when picking up a map? They try to figure out what area the map covers! The top-right margin of USGS maps reveals the quadrangle, political boundary area, scale, and type of map. The map we’re working from is the Huntsville Quadrangle in Walker County, Texas and is a topographic map at a scale of 7.5 minutes, or 1:24 000–the most popular scale used by hikers, search and rescue teams, etc.

What’s the first thing most people do when picking up a map? They try to figure out what area the map covers! The top-right margin of USGS maps reveals the quadrangle, political boundary area, scale, and type of map. The map we’re working from is the Huntsville Quadrangle in Walker County, Texas and is a topographic map at a scale of 7.5 minutes, or 1:24 000–the most popular scale used by hikers, search and rescue teams, etc.

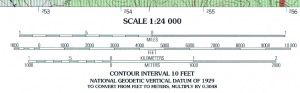

Knowing the scale of the map is important, but having a reference bar that facilitates “as the crow flies” distance estimation is even better. The scale can be found at the bottom center of the map. Here, the map re-enforces that a 7.5′ map is 1:24 000, and the three scale bars facilitate measuring distances in miles, feet, meters, and kilometers.

Knowing the scale of the map is important, but having a reference bar that facilitates “as the crow flies” distance estimation is even better. The scale can be found at the bottom center of the map. Here, the map re-enforces that a 7.5′ map is 1:24 000, and the three scale bars facilitate measuring distances in miles, feet, meters, and kilometers.

Measuring the distance on a two-dimensional printed map only estimates the distance; hence the reference to “as the crow flies.” This is because the topography of the environment isn’t considered; we live in a three-dimensional world. There is a difference in distance between a measurement on a map at the ocean’s edge versus a measurement across a mountainous landscape with perpetual ascents and descents. Remember, the focus of the series is on basic terrestrial navigation using a map and compass–so we aren’t going to talk about modern electronics that have the ability to compensate for these differences, that’s a future series.

![]() The scale bar doesn’t place the 0 at the left end like one might expect. Instead, the first portion of the scale bar is delineated to facilitate fractional measurements. Looking closely at the MILES scale, starting at the 0 moving left toward 1 there are alternate shaded bars. Each bar represents 1/10 of a mile. Similar shaded bars exist on the feet and meters/kilometers bar, though the FEET bar provides a less granular measurement at 1/20.

The scale bar doesn’t place the 0 at the left end like one might expect. Instead, the first portion of the scale bar is delineated to facilitate fractional measurements. Looking closely at the MILES scale, starting at the 0 moving left toward 1 there are alternate shaded bars. Each bar represents 1/10 of a mile. Similar shaded bars exist on the feet and meters/kilometers bar, though the FEET bar provides a less granular measurement at 1/20.

Contour Intervals and Quadrangles

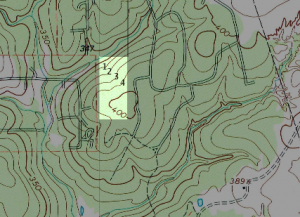

Immediately below the scale is another critical piece of information, the contour interval. Contrary to popular belief, Texas isn’t completely flat (and it isn’t all desert, either!). The distance between any two adjacent contour lines on this map represent a 10-foot elevation gain or loss. Looking at the shaded graphic, I’ve added text to count the lines from the 350′ contour line to the 400′ contour line. If you needed to travel from the top left corner of the un-shaded area to the center of the 400′ peak, you’d be gaining 50′ in elevation along the way.

Immediately below the scale is another critical piece of information, the contour interval. Contrary to popular belief, Texas isn’t completely flat (and it isn’t all desert, either!). The distance between any two adjacent contour lines on this map represent a 10-foot elevation gain or loss. Looking at the shaded graphic, I’ve added text to count the lines from the 350′ contour line to the 400′ contour line. If you needed to travel from the top left corner of the un-shaded area to the center of the 400′ peak, you’d be gaining 50′ in elevation along the way.

There are two other important pieces of information near the scale bar before we move on to the other information in the margins. First, the elevation model is based on datum from a 1929 survey. This is critical (think of Mount Saint Helens) would elevation data be useful from 1929? Likely not, since the mountain blew its top the elevations in the area have changed dramatically. The second useful bit of data is a friendly reminder of how to convert feet to meters, multiply by 0.3048.

What exact area does the Huntsville Quadrangle cover? Immediately to the right of the scale is an outline of the political border for the great state of Texas. This obviously generalizes the location. Looking at the four corners of the topo map reveals the latitude and longitudinal coordinates for each corner, as well as UTM data (which will be covered in a future series article).

What exact area does the Huntsville Quadrangle cover? Immediately to the right of the scale is an outline of the political border for the great state of Texas. This obviously generalizes the location. Looking at the four corners of the topo map reveals the latitude and longitudinal coordinates for each corner, as well as UTM data (which will be covered in a future series article).

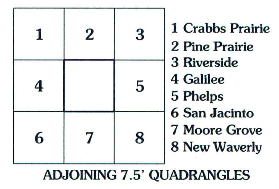

Let’s assume for a moment that you’re interested in hiking around the entirety of Lake Raven, located immediately above the Texas quadrangle location reference. How does one go about finding the next map to the immediate south of this location? Immediately below the quadrangle location is a very handy reference that shows the adjoining 7.5′ quadrangles. To ensure adequate coverage, we’d likely need to acquire the Moore Grove quad in addition to the Huntsville quad.

Let’s assume for a moment that you’re interested in hiking around the entirety of Lake Raven, located immediately above the Texas quadrangle location reference. How does one go about finding the next map to the immediate south of this location? Immediately below the quadrangle location is a very handy reference that shows the adjoining 7.5′ quadrangles. To ensure adequate coverage, we’d likely need to acquire the Moore Grove quad in addition to the Huntsville quad.

Legends and Declination

Moving still further right along the bottom margin of the Hunstville quad is a simple legend, or table of symbols found on the map. Unfortunately, this is rarely an all-inclusive legend. I printed and carry the USGS Topographic Map Symbols reference behind my map in my map case. Carrying an additional two sheets of paper in my load is negligible, and the ability to quickly reference rarely seen contour symbols, boundaries, coastal features, etc. is nice when you’re on an extended trip through the backcountry.

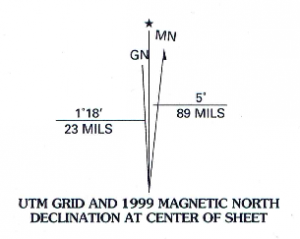

Located to the immediate left of the scale is the magnetic declination diagram, as calculated from the center of the sheet in the survey year. This diagram shows the angular relationship between Grid North, True North, and Magnetic North. We will cover Grid North in a future series article covering UTM. Likewise, a future series article will focus entirely on the venerable compass, including how to adjust the compass to take into account magnetic declinations.

Located to the immediate left of the scale is the magnetic declination diagram, as calculated from the center of the sheet in the survey year. This diagram shows the angular relationship between Grid North, True North, and Magnetic North. We will cover Grid North in a future series article covering UTM. Likewise, a future series article will focus entirely on the venerable compass, including how to adjust the compass to take into account magnetic declinations.

Magnetic declination takes into consideration that the Earth’s poles are constantly shifting. I’m neither a geophysicist, nor did I spend the night at a Holiday Inn- so I’m not going down this rabbit hole any further! Suffice to say, knowing the current magnetic declination for the area you’re heading into is particularly important- your compass is going to point to magnetic north, not true north. If the map was printed years ago, the amount of magnetic shift could be very significant.

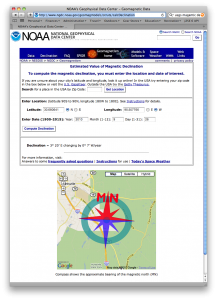

One of the most valuable utilities I’ve found for computing magnetic declination before heading into the backcountry is at the NOAA web site, Magnetic Declination Calculator. This calculator allows you to find the current or future (and presumably the past too) magnetic declination by entering in a specific lat/long, or a zip code if that’s all you have available to you.

One of the most valuable utilities I’ve found for computing magnetic declination before heading into the backcountry is at the NOAA web site, Magnetic Declination Calculator. This calculator allows you to find the current or future (and presumably the past too) magnetic declination by entering in a specific lat/long, or a zip code if that’s all you have available to you.

It then asks for a date, so if you are planning your trip for next summer, you can predict the declination for that point in time. In the example, we see that the Huntsville quad declination for 26 September 2010 is 3 ° 20′ E, changing by 0 ° 7′ W per year.

Declination Apps

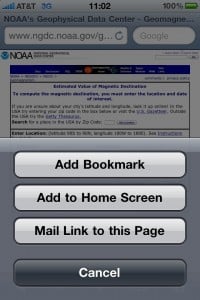

As an aside for those of you with an iPhone, it is possible to turn this calculator into an app icon on your main screen in 4 simple steps, saving you from having to remember the URL every time you want to look up a declination.

As an aside for those of you with an iPhone, it is possible to turn this calculator into an app icon on your main screen in 4 simple steps, saving you from having to remember the URL every time you want to look up a declination.

- Launch Safari and search from NOAA Declination Calculator and select the correct www.ngdc.noaa.gov calculator search result to display the page

- Click the + button to create a bookmark

- Choose Add to Home Screen

- Enter a name, e.g. Mag Decl

There are also a few apps in the AppStore that provide you with your current declination based on your current GPS location or searched location, but we haven’t tested these in depth yet. Just search “declination” in the Apple AppStore to get a look at these.

Notes

Everyone reads the margins of a map to figure out if the map contains the right information for the area of interest. Our next article will shift from the margins to the data found on the map itself. We’ll be discussing both map colors and terrain feature identification.

The LandNav 101 series is using the Sam Houston National Forest as the training grounds for most of its cartographic adventures. If you’d like to download a PDF of the referenced topo map, it is the Huntsville 7.5 x 7.5 1997 map. It has an alternate ID of TTX1823, ISBN 978-0-607-93473-1. A printed version can be purchased from the USGS Store for $8.

Discussion